by Eric Eidsness | May 10, 2021 | Blog

In many ways, pollution control was a political football.

Book excerpts:

- We were being hoisted on our own petard by a bunch of unaccountable White House bureaucrats assigned to OMB.

- There was no meaningful standard operating procedures and information management system to back it up when the Reagan/EPA was installed. This set up a no-win for the Reagan EPA leadership, including me, no matter what our enforcement posture was or perceived by Reagan’s political opponents.

- Ronald Reagan’s political enemies seized his Achilles’ heel, the EPA, and aligned their interests and message to demonize Anne Gorsuch. Their goal — to politicize EPA as a means of getting to the President and weaken him for the next election. They were willing to sacrifice EPA and its mission rather than debate and improve the means and methods of environmental protection moving forward. They played into the pathos of some EPA staff and magnified their belief that they were singled out and unjustly beleaguered by budget cuts and threats of forced separation — unjust because of the self-evident importance of their mission. Loss of staff moral became a self-fulfilling prophecy. In the end, however, Anne handed them the prize.

- Reagan’s political enemies had a problem. Reagan was likable and very popular as a person. He forged a strong bond with Tip O’Neil, the Democratic Speaker of the House, and was willing to compromise. It was doubtful that the liberal elite could get the traction to blunt Reagan’s agenda in all but the EPA. Hence, the very shrewd people who populated the echelons of the environmental lobby focused on bringing down Gorsuch by birddogging everything she did and used the print media to amplify their central allegation. Reagan’s political opponents agreed on this slogan to characterize our actions: “Backing away from enforcement of environmental laws.

- Environmentalists pointed an accusing finger at Anne and the rest of us for mismanagement, even while ignoring the overwhelming evidence that the Carter Administration had left us with a staggering backlog of unfinished business — a chronic problem each predecessor EPA administration passed on to their successor. Mismanagement at EPA was chronic since its inception owing to insufficient budget, personnel, impossible statutory or court ordered deadlines to write regulations, and most importantly, the lack of continuity in senior management owing to the revolving door of its political leadership who were appointed by the President.

- In the end, the Contempt of Congress citation that really had nothing to do with Anne or me, and Rita’s firing were the two events that brought down the house. This was not Anne’s fault, certainly not my fault. It was Ronald Reagan’s.

- I had lost my idealism, EPA was a political animal, and the environment just another political issue. It was never about EPA or its leadership or the policies we tried to put into place. They were only the vehicles to a bigger prize. It was about political power and the willingness to sacrifice any federal agency in the name of power and partisan politics. This message resonates today.

- Senator Howard Baker (R-TN), Senator Robert Stafford (R-VT) and Senator John Chafee (R-RI) seemed oblivious to the realities of what was going on in society regarding the EPA, and the rising chorus of criticism of EPA by many of their constituents. Their cry for bipartisan support for EPA and how it conducted itself was subsumed by a one-size-fits-all viewpoint devised by the environmental elite, who controlled the narrative that pressed for ratcheting down on technology to achieve zero emissions of pollutants without adequately weighing the costs or benefits of doing so or tradeoffs on achieving or supporting other values in our society; and who fundamentally distrusted states. If one did not subscribe to this worldview, then one was a partisan.

- To those critics who are suspicious of local people and local governments, and who believe that all good things come from the Federal Government on the banks of the Potomac River, this is proof that you are wrong!

- Congress was correct in making 208 areawide water quality management planning a national priority. However, the language of the statute confused the importance of linking management agency designation with land use and police powers. The timelines mandated by Congress for initial plan development were wildly inadequate, given the scope of the study, and completely out of sync with other major regulatory provisions of the 1972 Act. EPA’s implementation of 208 exacerbated this problem, and sent mixed signals to local governments as to what the singular priority of the Clean Water Act was — to meet the fishable-swimmable goals, as expressed in state Water Quality Standards. With agricultural and urban non-point sources of pollution causing impairment of uses today, Section 208 needs rebooting.

- As long as we are an industrial consumer-oriented society, we will create wastes, try to recover or recycle what we can economically justify from the wastes, and dispose of residual wastes on the land, in the air, water, estuarine, and marine resources. This cannot be accomplished without the full cooperation of state and local government. These are not only command and control solutions promulgated by the EPA in Washington, D.C. They require attention by general purpose government with police and land use powers under a planning process that is indeterminate in time, that is institutionalized into the multi-faceted responsibilities of local governments where strict accountability to the electorate remains.

by Eric Eidsness | May 10, 2021 | Blog

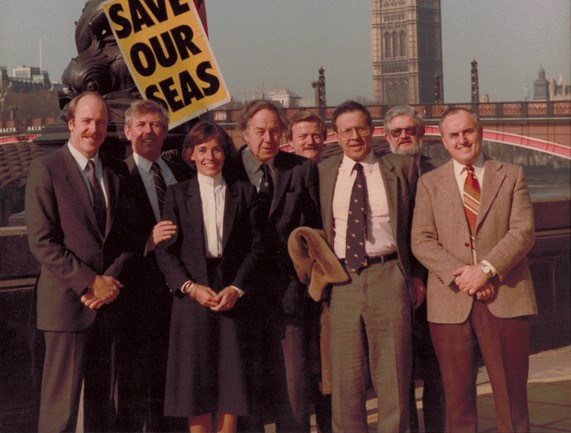

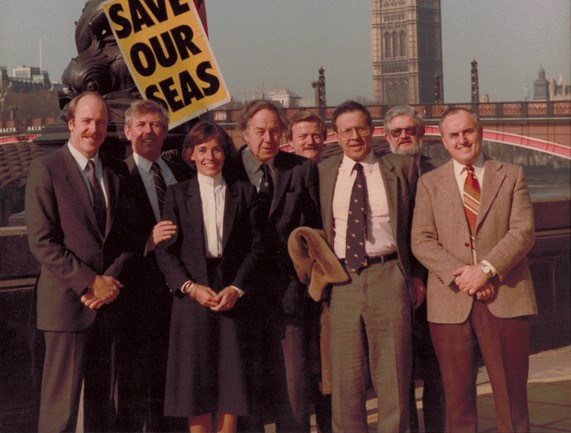

Photo description: London Dumping Convention January 1983

What was the blowback from the regulated community resulting from the 1980 presidential election?

Book Excerpts:

- By the time of the Reagan Administration, EPA had earned a reputation with many states, local governments, and the regulated community as confrontational, arrogant, and condescending, suborning science to pure ideology, perusing a regulatory agenda of “writing all the laws allow” in a manner that was overbearing, over prescriptive, often confusing and more. EPA was a federal agency with little accountability and lacked perspective of the social and economic forces that underwrite environmental protection decisions at the local level and the state and local institutions responsible for taking action…

- Admittedly, there was widespread support for achieving goals. Who doesn’t want clean air or water? However, there was widespread growing criticism from the regulated community and scientific and engineering advisors, and from many states that the means and methods EPA employed to roll out environmental statutes during its first decade were overbearing and confrontational when conversation and collaboration would have been more effective; whether the benefits outweighed the costs.

- EPA’s first two Administrators committed to an annual written strategy document for implementing the 1972 Federal Water Quality Administration (FWQA) during its first decade of water pollution control. The document set forth both good and counterproductive priorities; in the end, it had mixed results, and the unintended consequences proved to be dire on EPA’s reputation with industry and their scientific and engineering advisors. Though imperfect, the strategy was an attempt to communicate priority actions by the leadership, but the practice died under the Carter EPA.

- “Well, the agency (EPA) policies impose some very severe burdens. The basis of the approach, the policies that have been adopted over the years since the 1972 legislation was passed, overlook the basic concept that was contained in the legislation itself, and that is that the states are clearly vested with the responsibility for water quality standards, with the U.S. EPA given an oversight role where states do not proceed with the responsibilities as it’s envisioned in the act. Now, this relationship was not being achieved. What we had was referred by some as a parent-child relationship and others as a master-serf relationship”. Leo Weaver, Ohio River Water Sanitation District Board MacNeil/Lehrer Report, “EPA’s Muddy Water’s, Televised October 19, 1982 the day EPA issued its draft reforms to Water Quality Standards.

- “Well, unlike my colleague from Ohio, we do consider this a retreat. However, we are not so concerned with the state’s ability to provide flexibility or to make its own decisions. I think the issue is at a much higher level. It’s at the political level. Frankly, we see this as a retreat in the federal commitment that was made in 1972 for a federal presence in our water pollution control program. We in California have effectively used EPA as somewhat of a gorilla in the closet.” Clint Whitney, California Water Resource Control Board.

- If I hear one more time a top government official say as a justification for more top down policies on the environment, I will go screaming into the night. Everybody wants clean air and clean water, who doesn’t – at least conceptually. Unless and until local people understand how it effects them personally, support by the citizenry may in the end be tepid at best. This is a warning to the Biden Administration.

by Eric Eidsness | May 10, 2021 | Blog

Here’s a closer look behind the organization — the mindset and rationale of the agency.

Book excerpts:

- Jack Ravan (my boss and regional administrator in Region 4, Atlanta) was one political patronage appointee with no background or training whatsoever that even remotely related to EPA’s mission. The scuttlebutt among career employees, including my boss Joe Franzmathes, who frequently spoke to me as a confidant, was that EPA was not going to be a regulatory agency driven by science, engineering, and technology. It was, instead, a political organization that would suborn science and technology if politically expedient to do so.

- Those EPA behaviors borne of hierarchical thinking interfered with building a lasting coordinated partnership with states and local governments and making the means and methods of implementing environmental law more cost-effective by assuming a more inclusive posture on policy making, particularly inclusive of states and the regulated community and their scientific and engineering advisors who are burdened in carrying out EPA mandates.

- Of all the problems and challenges we faced was the untimely, confused, and generally poor direction that came out of EPA in Washington, D.C. I have covered this subject in detail in previous entries of this account. EPA personnel perched on the banks of the Potomac, in particular, view the world through the long lens of a telescope and delude themselves into believing that they actually understand how the world at the local level works. They never get the big picture, are quick to judge others, and dismiss their own ineptitude.

- Enthusiastic new headquarters middle managers who controlled the day-to-day expenditure of human and consulting resources seemed hell-bent on trying to write regulations and guidance that anticipated every problem that might arise, and prescribe a solution or requirement. During my tenure, the Office of Water had nearly $60 million in funds for contracting to consultants to assist HQ in rule making and writing “guidance.” This did not include funds allocated to consultants under the budget of the Office of Research and Development to support rule making by the Office of Water.

- Local governments have since illustrated their commitment to environmental protection in other areas by budgeting subjects that matter, such as converting public transportation rolling stock to natural gas, and providing financial incentives for local residents to purchase energy-efficient appliances, or sell geothermally and solar generated surplus electricity back to the public electric utility. One cannot argue that the state of sustainable living policies today has emerged from local initiatives, often in partnership with industry and not from federal mandates. The creativity and commitment to doing the right thing in terms of water pollution control, found at the local level — other than providing basic sanitary sewer service — has been sidelined too long. I trust it will re-emerge as we as a nation finally tackle climate change by converting our economy to a clean energy economy, not a fossil fuel economy.

- Regional offices became fiefdoms defined by the experience, personality and management styles of their RAs and top managers.

- Finally, my father wrote, “If protecting the environment is as important as we say it is, why do we not find men of Nobel Laureate status near the top? I am greatly disappointed at the failure of the Administration to seek out the very best men to lead technical efforts.”

- I was to learn the prevailing view of what I will refer to as the “Eastern establishment” — a terse and critical opinion of Westerners’ misguided attitudes towards water resources, such as sucking at the Federal teat of pork barrel water development projects.

- Another eastern establishment opinion was that of the Environmental Protection Agency’s approach to water quality-based planning and management that flew in the face of common sense from the western perspective. It demonstrated a total ignorance of, and disregard for, the law of prior appropriation under the State of Colorado’s Constitution. This issue alone would make the Larimer-Weld 208 Study controversial. When I made these conflicts known in an attempt to mitigate the conflicts, I eventually drew fire from a coalition of environmental organizations that charged me for “misusing federal funds to subvert the purposes of the Clean Water Act” and demanded an audit of my program and how the federal grant was being spent.

- The Hit List was a shock to western water users, including Coloradans.

It should surprise no one that President Reagan won all western states, and Carter none, in the 1980 Presidential Election. I believe this owed, in part, to Carter’s policies on western water resources development, to the Carter Hit List, and to EPA’s mishandling of the irrigated agriculture permit issue.

- While our new environmental leaders on the national stage are trying and the press and experts are attempting to talk to concerned activists, no one is talking to the average American in terms they understand; thus without understanding their political support for new initiatives will be cool at best, especially when they learn how it impacts their livelihoods and pocketbooks — at least, yet!

by Eric Eidsness | May 10, 2021 | Blog

In Eric’s office that overlooked the Capitol dome with Dr. Tudor Davies

Here I share insights into the top-down EPA hierarchy of the early 1980s…

Book excerpts:

- Little did I realize at the time that organization and key management decisions, including omissions made by EPA’s top political leaders in Washington, D.C. at the same time, were making the same decentralization decision and similarly taking a hands-off or laissez-faire attitude towards fulfilling the need to develop standard operating procedures in areas vital to EPA’s success and driving them through the hierarchy, from HQ to the 10 regional offices and 57 states and territories. Rather than grow into the job as a strong organizational manager, Jack became the penultimate “politician.” His behavior seemed motivated to not come down on the wrong side of an issue.

- Without meaningful priorities set by the AAs and a system to evaluate performance against those priorities, performance standards would devolve into the AA just telling his office directors to set their own priorities. The whole exercise would be easily gamed to produce “performance exceeding expectations,” the highest ranking under Rebecca’s system.

- EPA is led by an ever-revolving door of political appointees and lacks accountability for its actions and failures. In my case, I also instituted the first standard operation procedures and accountability system that pushed national priorities through EPA’s 10 regions and 57 states and territories upon which I could evaluate performance, report accurately to Congress, and make management improvements. This vital management tool disappeared because of the frequent turnover of top EPA officials who serve the President “for the time being”.

- Initially, the only check-and-balance over regulatory creep was Congress’ oversight authority, which varied considerably over the years and was only marginally effective at checking EPA’s excesses. Indeed, in the first two decades of EPA’s rollout of the CWA, Congress was interested in expanding its activities, not restricting its activities.

- From this dissertation, one can appreciate the consequences resulting from EPA being formed as a political organization under executive order where its top leadership who served at the pleasure of the President for “the time being” were seldom in office long enough to see the results of their policies, make corrections, and ensure new programs established by their predecessors did not lose top management attention by their successors. To be sure, the organizational decisions, management and communication style, and policy emphasis of the first three EPA Administrators of the 1970s had much to do with EPA’s acute operating inefficiency, its inability to remain faithful to the laws it administered as corresponding regulations were rolled out, programs put in place to implement them, and organizational accountability (or lack thereof). Ruckelshaus’ management imprint was most influential. While achieving some desired outcomes, there were unintended adverse consequences of EPA’s early policy and organizational decisions that will be chronicled in the ensuing chapters in this Part II.

- What I am referring to by the term “standard operating procedures” (SPO’s) is the means and methods by which “span of control” of managers, starting with the Chief of Naval Operations, were able to effectively carry out its mission despite its size and physically decentralized global force. Without written standard operating procedures, the span of control of an EPA administrator or regional administrator would be the number of people he or she could meet with or number of phone calls made in a day. Consequently, heavy reliance was made on the fealty of the recipient of a policy in carrying out directives from the top of the organization — fealty that was in the case of EPA, misplaced particularly in light of countervailing policies that emanated from a decentralized agency consisting of 10 regional offices. Memos that he/she might issue in EPA’s headquarters and signed by the administrator could be ignored or not disseminated in the organization below the managers. Thus the rank and file was often oblivious to policy shifts.

- EPA needs to be reoriented towards serving less as a political beast of the White House or the majority party administration, and more as a true independent scientific and technological organization with a mission and wherewithal in alignment. This will require acknowledging that the challenges EPA faces today are very different than in 1972. We have made great strides in enhancing and protecting the uses supported by water quality. The institutions of government, particularly at the state level, are better equipped to foster a new generation of pollution control strategies.

- Indeed, over EPA’s history, with the exception of formal rule making under the Administrative Procedures Act, adoption of administrative policy statements and guidance did not follow any prescribed process (until my tenure — see Part IV: Sewergate) and each office typically published its own guidance and policy statements on an ad hoc basis without benefit of any formal review or approval process, such as the Red Border Review Process.

- EPA needs to be rebooted to meet the realities of our times.

by Eric Eidsness | May 10, 2021 | Blog

Here’s a peek behind the scenes in the heady days of the Reagan years.

Book excerpts:

- Hubris is the bane of all new political appointees who feel they have all the answers and their predecessors did everything wrong. Having all the answers but not knowing what the question is, is quicksand.

- The lesson is clear: with EPA’s revolving door of administrative and regional administrators, it seemed that a system of management accountability could not be effectively carried out at EPA. Thus In 1993, Congress passed and President Bill Clinton signed into law — The Government Performance and Results Act (Pub. L. 103-62).

- The EPA must be clearly focused on implementing existing laws and regulations, and on a more effective nationwide enforcement system (including oversight of state compliance activities under delegation agreements). We must ensure that investment of our treasury in past and future pollution control (particularly from point sources) actually achieves its designed goals. Also, research in all media must be consolidated and oriented toward emerging environmental problems and serve to reinforce new regulations or regulatory reform, not remain detached from media program pursuits. While enhancing our ability to monitor and detect both environmental trends, we must also ensure the effectiveness of our institutions to meet their objectives. American citizens have a right to expect a higher standard of implementation and enforcement than in the past, with states on the front line, not EPA.

- I believe that the root cause of the problems EPA created or encountered in rolling out the CWA, the effluent guideline, permits and enforcement program in particular, and its seeming inability to make its own policy corrections, stem from the revolving door of EPA leadership, beginning with Ruckelshaus’ departure in April 1983. His successor, Russell Train, could not have understood the complexity of the issues resulting from the Water Policy Paper; the ship had sailed, so to speak, and no one was going to challenge EPA’s course — not even the GAO or the Congress.

- If you believed what you read in the mass printed media — that the top presidential appointees who followed Anne McGill Gorsuch to EPA in 1981 were ideologues, bad people, unqualified and basically bereft of intellect or ideas, you would be wrong. There was, however, one exception.

by Eric Eidsness | May 10, 2021 | Blog

Here I share snippets of opinion and interesting viewpoints from the book.

Enjoy!

Book excerpts:

- My father always joked, “You pull the chain, we do the rest.” As the son of a sanitary engineer who cast a big shadow, I had to define myself, what kind of a professional engineer I would become, and why. I became a P.E. of a different sort — a “political engineer.” I meant to bring that perspective to Washington, D.C. where my father was born and where three generations of Eidsness men had served honorably in the service of their country.

- Those early years of EPA were heady. We were idealistic, focused on our mission of protecting public health and the environment. The overall view of the legal requirements and direction provided by EPA’s HQ leadership, however, was simplistic and often misdirected, at best. Despite the complexity of the task, which resulted in huge transaction costs imposed on the states and regulated community; there were great results in reducing pollution loads from entering the waters of the United States during the 1970s.

- I learned after the fact that what I did not know before I returned to EPA in September 1981 would at the least blindside me about how to engage with the Congress and my critics in a debate over reforming WQS as an effective regulatory tool, but indeed resulted in mistakes of my own making. I was well equipped to propose technical changes to the means and methods EPA/states used to adopt and implement WQS, but not on firm ground regarding certain policies because of my engineering orientation and lack of public policy experience at the national level.

- To me, EPA seemed more like a social experiment for politicians and hardcore environmentalists to practice social science in a new field of public policy, rather than a regulatory agency that placed the protection of public health and the environment above all. I know my father felt the same way. As a consequence of this transformation, many in the new EPA found that although there was a personal thrill, if adrenaline rush, resulting from being at the apex of a hierarchy directing the implementation of federal laws, a cold dose of reality ensued as the power plays and “transactions” involved seemed more important than the results achieved.

- The experience of being in the center of power in a change of administrations was heady, but I didn’t lose my bearings and focused on doing a better job of managing my department. What surprised me most was the enormous backlog of responsibilities that awaited me. Also, career civil servants were tensely anticipating a new group that represented a President who was decidedly anti-big government, wanting to please the new president, but unsure what that meant. I already knew many of the Office of Water personnel. So I met the “team” and set my agenda.

- I can say with some authority that engineers view all environmental problems as ones that require a “technical solution.” Indeed, engineers are problem-solvers; our institutions of higher learning train us to do this. The engineering profession holds us to a high standard of accountability, as I mentioned before. Hence, problems have technical solutions, which should be self-evident. However, local political decisions to finance an ongoing effort under 208 rarely hinge on the “technical solution.” We have also witnessed how decisions at the federal level, even congressional decisions, are less concerned with science and technology than they are with career-building; often their decisions reflect the world as seen from a hermetically-sealed bubble.

- I am an engineer, but a political engineer, who believes the solution to our environmental problems begins, not with the technical answer, but with institutional alignment on the problem statement and an open process of decision-making. Then, the best technical solution will surface. My reforms came from grassroots planning effort backed up by superior technical analysis and innovative thinking, where we had to make sense out of the often-nonsensical State of Colorado and EPA directions we were given, and in reliance on EPA actions that did not materialize in time for us to incorporate them into our plan. We determined that the framers of the ’72 CWA gave us a framework that could effectively work to protect water quality, even in the face of ambiguity, court decisions that defied common sense, and distrust of states by our national leaders.

- Caught between “a rock and a hard place,” 208 Directors had run the gauntlet between the sometimes-idealistic demands of officials of the EPA and the State of Colorado, and the pragmatic view of local interests who wanted to understand the costs and benefits of proposed controls before committing to their implementation through public and private (industry) financing.

- My critical analysis of EPA in its first decade is something I didn’t plan to do when I set out to write this tome, but it meets with my philosophical beliefs that we have to understand the full dimension of the problem before we can devise better strategies as solutions.

- I cannot risk the temptation of editorializing Howard Baker’s quote regarding how the American economy multiplied as did automobiles since the instigation of environmental laws. Perhaps he didn’t understand that an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.

- My immediate supervisor, Joe Franzmathes, walked into my office and said, “I know why you didn’t accept Jack’s offer. You don’t respect Jack, do you?” I shrugged off the question because Jack was only symptomatic of a bigger problem that Joe was also part of. I do remember that I had good reasons to be disenchanted with federal service. I was only 26. I did not appreciate, until I served in a top EPA management position a decade later overseeing policy, management, and budget, the enormous challenges faced by EPA’s leadership during the 1970s and the difficult choices they had to make to roll out new environmental statutes.

- In retrospect, my experience as a presidentially-appointed, Senate-confirmed Assistant Administrator in the EPA was my military service in Vietnam and the San Francisco Bay Area revisited, at least on an emotional level. In both instances, I was in a war zone. When it was over, I felt blamed for my service, my fealty to the Oath of Office was ignored if not respected, and I was left with a dark cloud looming over my head that had a serious impact on my ability to grain employment to support my wife and three young children and with nothing meaningful to do.

- I warned Ruckelshaus that the President needed to enunciate his policy on the enforcement of environmental statutes generally, at the least to align his own political appointees and to reassure the staff and public that he wanted enforcement. I made this bold statement in light of the comments made by President Reagan regarding his expectation of the Ruckelshaus II tour at the time of Ruckelshaus’s swearing-in in the Old Executive Office Building, which fell far short of this. There is no indication that his message was trumpeted either by the career staff, or in the media.]

- Bill’s response to all this was, ‘Don’t you worry about EPA, let me worry about that; that’s my job.’It was an insulting and patronizing remark … well, the rest is history. There remains no Reagan environmental policy. Ruckelshaus is leaving … Bill’s departure, as with his return to EPA, was a script made for Hollywood. His goal seemed to be to restore morale — I hope he succeeded, I regret I could not have been a part of the rebuilding, though I know now I did not fit in a Ruckelshaus team … Reagan has failed to show leadership altogether in the area of environmental protection, which perpetuates the lie and dangerous mentality that a safe environment and economic growth are mutually exclusive concepts. Politicization of the environment — though others contributed substantially to this outcome — is the Reagan Legacy.”