Photo credit and permission © George Dow, courtesy of Bradford Washburn Family Collection. All rights reserved.

The Washburns

In 1959, my parents shipped me off to New England to escape the racism of the Deep South and to get a “real education.” Through my mother’s sister, Barbara Polk Washburn, and my Uncle Bradford Washburn, my parents enrolled me at Holderness Preparatory School in the fall of 1959.

It was a lonely 24-hour train ride on the East Coast Champion or the Silver Meteor from Stark, Florida, the nearest station to Gainesville, to Boston; then on to a New England rail line to Concord, New Hampshire, where the school administration had a van waiting. In the winter of 1959/1960, New England experienced record cold and snowfalls. It was all a cultural and a climate shock for me. Many of my classmates were trust fund babies, and I was the first “rebel” to enroll in this prestigious 80-year-old private school.

During the two years I attended Holderness before I returned to Gainesville High School in 1962, owing to my father’s battle with cancer, Brad and Barbara functioned as my surrogate parents. They lived in Cambridge, Massachusetts on Brattle Street, in an enormous white wood Victorian three-story house – just a few blocks from Harvard Square. Robert Frost lived in a house behind theirs, and I remember the famous poet laureate shuffling around their wooded circular driveway, mumbling to himself.

My good fortune as nephew of Bradford Washburn was that he was the founding Manager of the Boston Museum of Science, one of the great learning museums of the world. Brad and the Boston Museum of Science partnered with the National Geographic Society for his entire professional life on mapping expeditions, including Alaska’s Denali (Mt. McKinley), the Grand Canyon National Park, Mt. Everest, and the Himalayan Range. Brad was a mountain photographer of some renown. Though the photos were artistic by professional standards, Brad’s motive was to photograph the areas he was mapping in order to reconcile data or interpolate data points regarding drawing topographic lines. Ansel Adams was a close friend and colleague who, according to Barbara, encouraged Brad to sell his photographs. Years after Adams’s death, Brad published photographs of the McKinley Range in a book featuring his large-format Kodachrome full-color photos; the Preface was written by Ansel Adams, who clearly respected Brad’s work and anticipated that Brad would publish his photographs one day.

Often Brad explored mountains with Barbara in tow. Through him, I was exposed to the science of the natural world. When I accompanied him on mapping expeditions, I learned the importance of scientific observation and the tedium and hardship of fieldwork.

The Photo

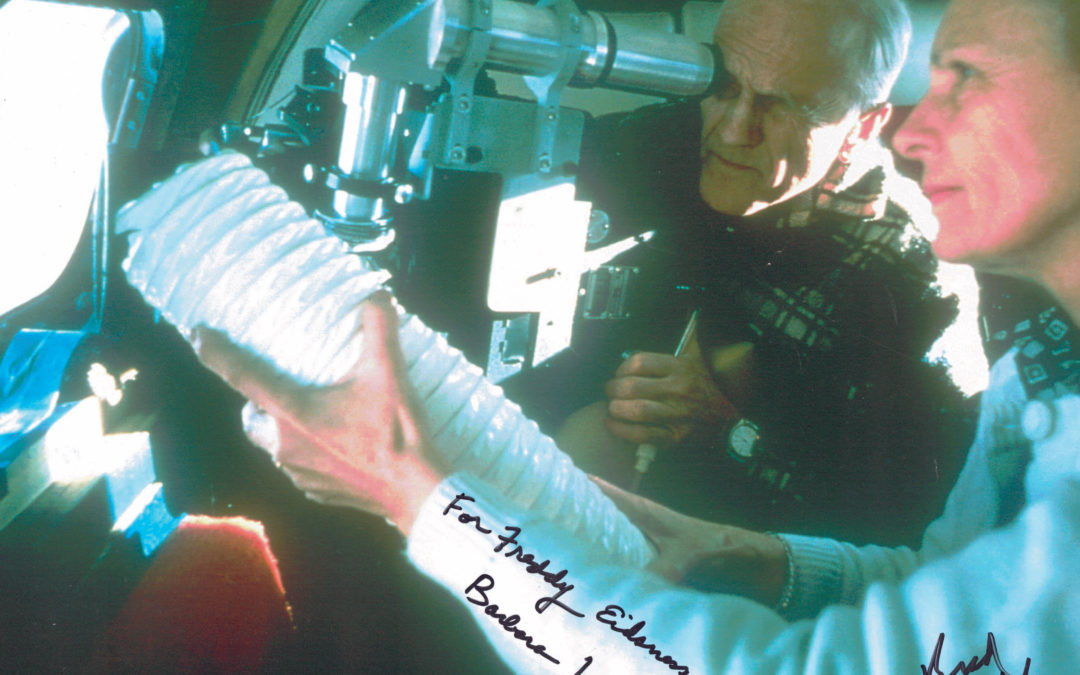

The iconic photograph I feature here, dated September 22, 1978, doesn’t have the best resolution but is one of my favorites. It was taken by George Dow and shows Uncle Brad and Aunt Barbara at work on a Learjet during a high altitude photo survey flight (41,000 feet) in Alaska over the McKinley wilderness. They were looking northeastward, almost at sunset. Barbara is holding a flex tube through which air is being blown to eliminate condensation. Brad is photographing through an optical glass window placed in the door of the Learjet. The window was provided by Edwin Land, founder and owner of The Polaroid Corporation, and a good friend of Brad’s.

I miss these two special people who were so instrumental in my formative years and inspirational in my adulthood. I thought of them often while writing Gorilla in the Closet, as they were environmentalists too.