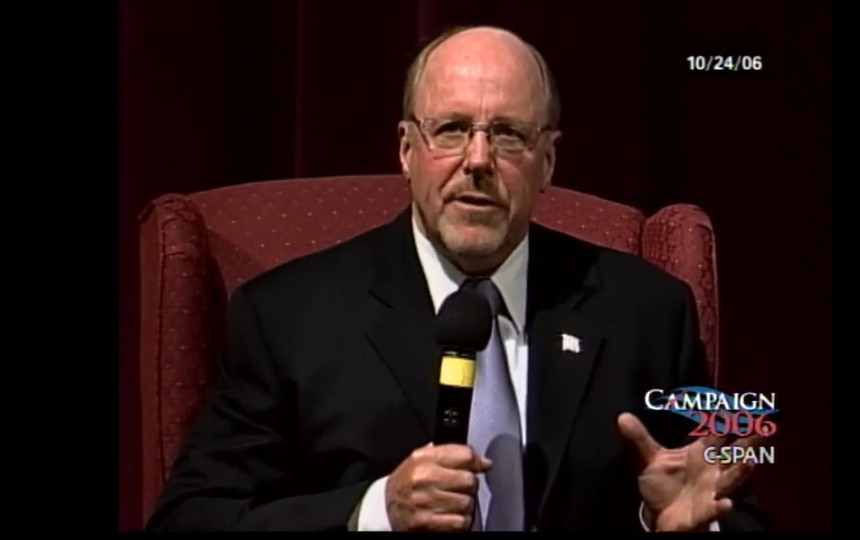

Eric Eidsness debates as a congressional candidate in Colorado’s 4th District on Oct. 24, 2006.C-SPAN

Former EPA official urges federalist revamp at agency

Reagan-era EPA official Eric Eidsness wants a new name, new structure and less politics out of his old agency, he wrote in his recently released book.

GREENWIRE | EPA needs a wholesale revamp to better protect the environment and more adeptly tackle climate change mitigation, according to a new book penned by a former high-ranking agency official.

The more than 750-page manifesto, “Gorilla in the Closet,” makes the case for what author and ex-EPA official Eric Eidsness dubbed “new environmental federalism.” Eidsness was confirmed as EPA’s assistant administrator for water in March 1982 under President Ronald Reagan.

“EPA is a political beast now — it always was, but never to the degree we see now, because the environmental lobby has captured the Democrats, and they never saw an environmental problem they couldn’t solve from the banks of the Potomac River,” he said in an interview. “And Republicans want to deregulate or abolish EPA altogether.”

The Fort Collins, Colo., resident, Vietnam War veteran and former congressional candidate says EPA should be reformed in favor of a less political, more effective agency to ensure environmental protection by working from the bottom up rather than from the top down.

“It needs to change from a political agency who reports to the White House to an independent commission and hire professionals who understand organizational management and accountability who are there long enough to maintain continuity,” Eidsness said.

Eidsness even advocates for a new name: the National Environmental Protection Commission, or NEPC. He says it would function more closely to how the FBI’s leadership operates and would have high-ranking officials serve 10-year terms rather than the current system tied to presidential administrations.

That commission would consist of 11 members, one of whom, the chair, would be a political appointee picked by the sitting president. Others would represent academia, science, business, environmental interests, civil rights, state and local leaders, and other interests, Eidsness said.

“Not of a political party but protecting public health and the environment using the best science and technology we can provide,” he added.

Eidsness also takes issue with EPA’s current organizational system, which consists of specialized program offices based in Washington, D.C., and 10 regional offices run by presidential appointees overseeing states and territories.

Instead, he proposes that each state have an ombudsperson who runs programs and that those leaders be chosen from the Senior Executive Service. Under the plan, each state — with its different industries, demographics, geography and overall priorities — could craft its own approach to environmental protection.

“We have to be concerned about who gets a chance to voice their opinion,” Eidsness said. “At the end of the day, if we don’t engage local people and local governments that have the vast majority of land use and police power over our nation to prepare for the worst effects of climate change and to reduce carbon locally through local codes and ordinances, there’s no way we can succeed.”

He says the book’s title, “Gorilla in the Closet,” refers to EPA’s “ambush mentality” of stepping in when states and local governments fail to act and its role as an enforcer rather than a collaborator or a partner.

In Eidsness’ view, the federal command-and-control regulatory system should be more collaborative so the “gorilla in the closet” can be more effective.

Firsthand experience

Eidsness feels he is well-positioned to criticize EPA bureaucrats because he once was one.

Soon after the agency was formed under the Nixon administration, Eidsness worked for EPA’s water quality predecessor, the Federal Water Quality Administration, as an inspector of municipal sewage treatment facilities.

A decade later, he was confirmed as EPA’s assistant administrator for water during the Ronald Reagan administration, where he served under Administrator Anne Gorsuch from 1981 to 1983.

His EPA era is often defined by the “Sewergate” controversy, when the head of the agency’s solid waste program, Rita Lavelle, was accused of misappropriating funds from the Superfund program.

At that time, Eidsness had policy, budget and management authority over the Clean Water Act; the Marine Protection, Research and Sanctuaries Act of 1972; and the Safe Drinking Water Act.

His signature regulatory reform was implementation of water quality standards that govern how local governments protect rivers, lakes and streams.

That experience and watching the agency’s objectives flip-flop between Washington-centric and decentralized with each change of administration influenced his vision for environmental protection that prioritizes local government’s role, he said.

The Biden administration’s signature legislation, the Inflation Reduction Act, despite its good intentions to combat climate change, is an example of a top-down approach, Eidsness said.

“They’re trying to create a demand to do things at local level by creating a huge supply of money, and the consequence of that will be massive fraud and abuse,” he said.

Instead, what Eidsness envisions is “a bottom-up strategy that establishes local, city- and county-administered programs that specifically address reducing carbon emissions and planning for the land use impacts of the worst symptoms of climate change — with the full support of the federal government,” or new environmental federalism, he writes.

“One size fits all is the mantra of the environmental lobby — I’m glad we did that back when I ran water program, that was necessary, but that was 50 years ago,” Eidsness said. “Now we have got to put more focus on bottom-up strategies.”

Looking to the future

How do you implement a bottom-up approach to addressing climate change?

Eidsness says the answer is reducing carbon emissions on the local level through economic incentives.

Unlike grant programs, tax breaks and other measures so far proposed by the Biden administration, they shouldn’t be one-size-fits-all. And he cautions that before supplying the money, you need demand.

Eidsness uses heat pump technology as an example. Home heating and cooling systems powered by oil and gas contribute to a lot of the carbon emissions in urban areas, which has led environmental advocates to push the energy-efficient alternative.

To create a “buzz” about heat pumps and get a program to subsidize the technology off the ground, governments will need to engage entities involved — real estate agents who sell houses; bankers who finance them; and heating, ventilation and air conditioning companies that would install the technology.

The same strategy goes for electric vehicles, flood insurance and other climate mitigation tools, he says.

Eidsness’ suggestions come not only from his experience as a policymaker, but from his own hopes for the future.

As a grandfather of five, he says, he fears for his grandchildren’s safety and health as soon as 20 years from now.

“We are failing as a nation today, and that’s becoming more and more obvious,” Eidsness said. “You cannot spend your way out of this problem. You have to change people’s thinking and enlist them in a cause they can support, and the only way to do this is a federalist model.”