by Eric Eidsness | May 10, 2021 | Blog

Here I share snippets of opinion and interesting viewpoints from the book.

Enjoy!

Book excerpts:

- My father always joked, “You pull the chain, we do the rest.” As the son of a sanitary engineer who cast a big shadow, I had to define myself, what kind of a professional engineer I would become, and why. I became a P.E. of a different sort — a “political engineer.” I meant to bring that perspective to Washington, D.C. where my father was born and where three generations of Eidsness men had served honorably in the service of their country.

- Those early years of EPA were heady. We were idealistic, focused on our mission of protecting public health and the environment. The overall view of the legal requirements and direction provided by EPA’s HQ leadership, however, was simplistic and often misdirected, at best. Despite the complexity of the task, which resulted in huge transaction costs imposed on the states and regulated community; there were great results in reducing pollution loads from entering the waters of the United States during the 1970s.

- I learned after the fact that what I did not know before I returned to EPA in September 1981 would at the least blindside me about how to engage with the Congress and my critics in a debate over reforming WQS as an effective regulatory tool, but indeed resulted in mistakes of my own making. I was well equipped to propose technical changes to the means and methods EPA/states used to adopt and implement WQS, but not on firm ground regarding certain policies because of my engineering orientation and lack of public policy experience at the national level.

- To me, EPA seemed more like a social experiment for politicians and hardcore environmentalists to practice social science in a new field of public policy, rather than a regulatory agency that placed the protection of public health and the environment above all. I know my father felt the same way. As a consequence of this transformation, many in the new EPA found that although there was a personal thrill, if adrenaline rush, resulting from being at the apex of a hierarchy directing the implementation of federal laws, a cold dose of reality ensued as the power plays and “transactions” involved seemed more important than the results achieved.

- The experience of being in the center of power in a change of administrations was heady, but I didn’t lose my bearings and focused on doing a better job of managing my department. What surprised me most was the enormous backlog of responsibilities that awaited me. Also, career civil servants were tensely anticipating a new group that represented a President who was decidedly anti-big government, wanting to please the new president, but unsure what that meant. I already knew many of the Office of Water personnel. So I met the “team” and set my agenda.

- I can say with some authority that engineers view all environmental problems as ones that require a “technical solution.” Indeed, engineers are problem-solvers; our institutions of higher learning train us to do this. The engineering profession holds us to a high standard of accountability, as I mentioned before. Hence, problems have technical solutions, which should be self-evident. However, local political decisions to finance an ongoing effort under 208 rarely hinge on the “technical solution.” We have also witnessed how decisions at the federal level, even congressional decisions, are less concerned with science and technology than they are with career-building; often their decisions reflect the world as seen from a hermetically-sealed bubble.

- I am an engineer, but a political engineer, who believes the solution to our environmental problems begins, not with the technical answer, but with institutional alignment on the problem statement and an open process of decision-making. Then, the best technical solution will surface. My reforms came from grassroots planning effort backed up by superior technical analysis and innovative thinking, where we had to make sense out of the often-nonsensical State of Colorado and EPA directions we were given, and in reliance on EPA actions that did not materialize in time for us to incorporate them into our plan. We determined that the framers of the ’72 CWA gave us a framework that could effectively work to protect water quality, even in the face of ambiguity, court decisions that defied common sense, and distrust of states by our national leaders.

- Caught between “a rock and a hard place,” 208 Directors had run the gauntlet between the sometimes-idealistic demands of officials of the EPA and the State of Colorado, and the pragmatic view of local interests who wanted to understand the costs and benefits of proposed controls before committing to their implementation through public and private (industry) financing.

- My critical analysis of EPA in its first decade is something I didn’t plan to do when I set out to write this tome, but it meets with my philosophical beliefs that we have to understand the full dimension of the problem before we can devise better strategies as solutions.

- I cannot risk the temptation of editorializing Howard Baker’s quote regarding how the American economy multiplied as did automobiles since the instigation of environmental laws. Perhaps he didn’t understand that an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.

- My immediate supervisor, Joe Franzmathes, walked into my office and said, “I know why you didn’t accept Jack’s offer. You don’t respect Jack, do you?” I shrugged off the question because Jack was only symptomatic of a bigger problem that Joe was also part of. I do remember that I had good reasons to be disenchanted with federal service. I was only 26. I did not appreciate, until I served in a top EPA management position a decade later overseeing policy, management, and budget, the enormous challenges faced by EPA’s leadership during the 1970s and the difficult choices they had to make to roll out new environmental statutes.

- In retrospect, my experience as a presidentially-appointed, Senate-confirmed Assistant Administrator in the EPA was my military service in Vietnam and the San Francisco Bay Area revisited, at least on an emotional level. In both instances, I was in a war zone. When it was over, I felt blamed for my service, my fealty to the Oath of Office was ignored if not respected, and I was left with a dark cloud looming over my head that had a serious impact on my ability to grain employment to support my wife and three young children and with nothing meaningful to do.

- I warned Ruckelshaus that the President needed to enunciate his policy on the enforcement of environmental statutes generally, at the least to align his own political appointees and to reassure the staff and public that he wanted enforcement. I made this bold statement in light of the comments made by President Reagan regarding his expectation of the Ruckelshaus II tour at the time of Ruckelshaus’s swearing-in in the Old Executive Office Building, which fell far short of this. There is no indication that his message was trumpeted either by the career staff, or in the media.]

- Bill’s response to all this was, ‘Don’t you worry about EPA, let me worry about that; that’s my job.’It was an insulting and patronizing remark … well, the rest is history. There remains no Reagan environmental policy. Ruckelshaus is leaving … Bill’s departure, as with his return to EPA, was a script made for Hollywood. His goal seemed to be to restore morale — I hope he succeeded, I regret I could not have been a part of the rebuilding, though I know now I did not fit in a Ruckelshaus team … Reagan has failed to show leadership altogether in the area of environmental protection, which perpetuates the lie and dangerous mentality that a safe environment and economic growth are mutually exclusive concepts. Politicization of the environment — though others contributed substantially to this outcome — is the Reagan Legacy.”

by Eric Eidsness | May 7, 2021 | Blog

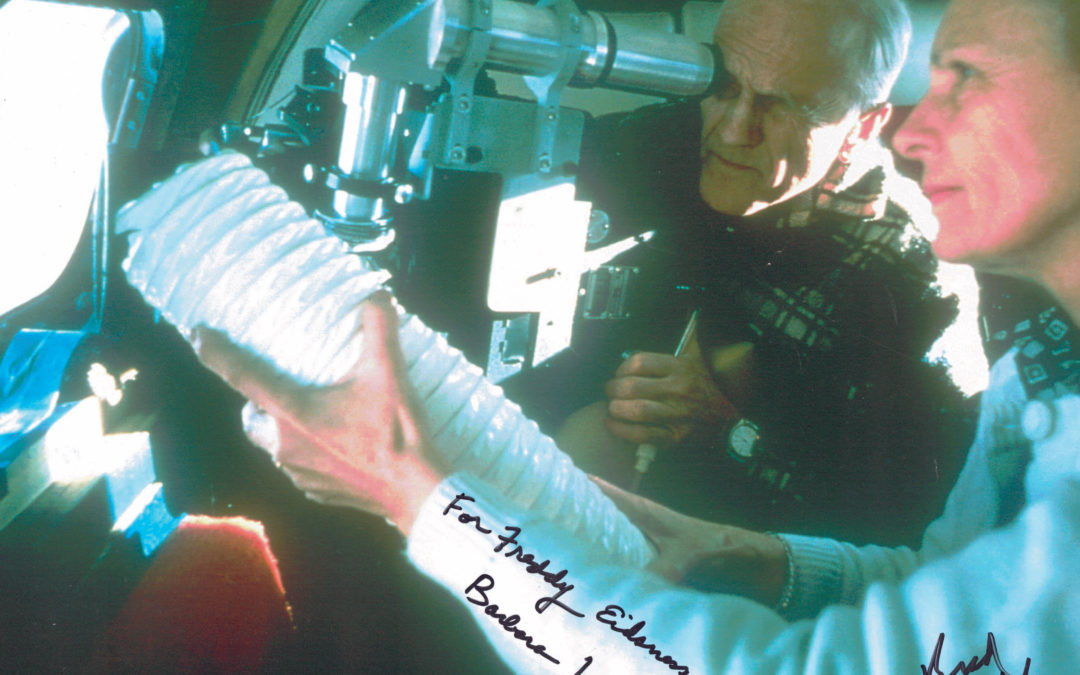

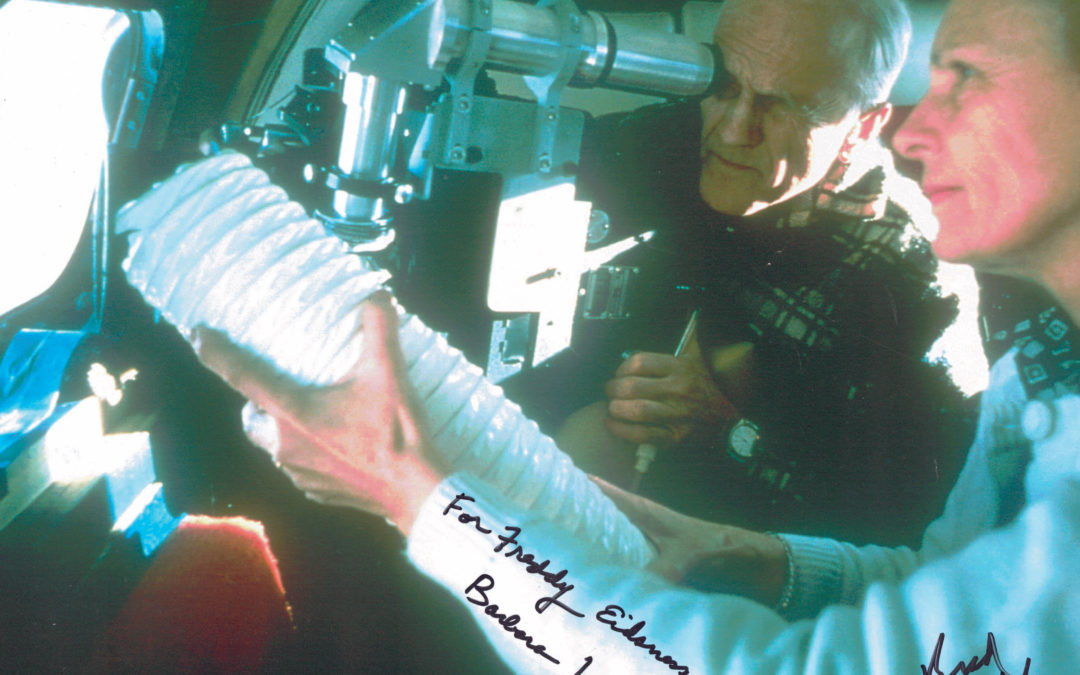

Photo credit and permission © George Dow, courtesy of Bradford Washburn Family Collection. All rights reserved.

The Washburns

In 1959, my parents shipped me off to New England to escape the racism of the Deep South and to get a “real education.” Through my mother’s sister, Barbara Polk Washburn, and my Uncle Bradford Washburn, my parents enrolled me at Holderness Preparatory School in the fall of 1959.

It was a lonely 24-hour train ride on the East Coast Champion or the Silver Meteor from Stark, Florida, the nearest station to Gainesville, to Boston; then on to a New England rail line to Concord, New Hampshire, where the school administration had a van waiting. In the winter of 1959/1960, New England experienced record cold and snowfalls. It was all a cultural and a climate shock for me. Many of my classmates were trust fund babies, and I was the first “rebel” to enroll in this prestigious 80-year-old private school.

During the two years I attended Holderness before I returned to Gainesville High School in 1962, owing to my father’s battle with cancer, Brad and Barbara functioned as my surrogate parents. They lived in Cambridge, Massachusetts on Brattle Street, in an enormous white wood Victorian three-story house – just a few blocks from Harvard Square. Robert Frost lived in a house behind theirs, and I remember the famous poet laureate shuffling around their wooded circular driveway, mumbling to himself.

My good fortune as nephew of Bradford Washburn was that he was the founding Manager of the Boston Museum of Science, one of the great learning museums of the world. Brad and the Boston Museum of Science partnered with the National Geographic Society for his entire professional life on mapping expeditions, including Alaska’s Denali (Mt. McKinley), the Grand Canyon National Park, Mt. Everest, and the Himalayan Range. Brad was a mountain photographer of some renown. Though the photos were artistic by professional standards, Brad’s motive was to photograph the areas he was mapping in order to reconcile data or interpolate data points regarding drawing topographic lines. Ansel Adams was a close friend and colleague who, according to Barbara, encouraged Brad to sell his photographs. Years after Adams’s death, Brad published photographs of the McKinley Range in a book featuring his large-format Kodachrome full-color photos; the Preface was written by Ansel Adams, who clearly respected Brad’s work and anticipated that Brad would publish his photographs one day.

Often Brad explored mountains with Barbara in tow. Through him, I was exposed to the science of the natural world. When I accompanied him on mapping expeditions, I learned the importance of scientific observation and the tedium and hardship of fieldwork.

The Photo

The iconic photograph I feature here, dated September 22, 1978, doesn’t have the best resolution but is one of my favorites. It was taken by George Dow and shows Uncle Brad and Aunt Barbara at work on a Learjet during a high altitude photo survey flight (41,000 feet) in Alaska over the McKinley wilderness. They were looking northeastward, almost at sunset. Barbara is holding a flex tube through which air is being blown to eliminate condensation. Brad is photographing through an optical glass window placed in the door of the Learjet. The window was provided by Edwin Land, founder and owner of The Polaroid Corporation, and a good friend of Brad’s.

I miss these two special people who were so instrumental in my formative years and inspirational in my adulthood. I thought of them often while writing Gorilla in the Closet, as they were environmentalists too.

by Eric Eidsness | May 6, 2021 | Blog

A Personal Note

In a three year period, I replaced the gas fired heating system in my residence, my daughter’s residence, and two income properties. My guilt as an environmental engineer is that I could not find an alternative electric powered heating system. I won’t be changing out these new units for decades, long after the 2030 target our president has set for achieving a 50-52% reduction in carbon emissions from 2005 levels. There should be an easy way. Gas is a significant source of greenhouse gases. If I learned anything working with local governments during my career, local people can be trusted to do the right thing if they understand their options, they are tangible and relevant and practical and contribute to a broader goal – in this instance, addressing climate change. My gift to the Biden Administration is an outline of a bottom-up approach to addressing global warming. It is vitally needed to engage and enlist the participation of ordinary people in our fight for survival.

Carbon Audit Program Overview

I propose a carbon audit program to build local public (political) support and participation for an aggressive and sustained national effort at achieving and sustaining carbon reduction targets to mitigate the adverse consequences of global warming. It prioritizes funding and CAP assistant to persons impacted by environmental justice sites and minorities in general. This is a ground-up strategy that depends on a complementary top-down strategy administered by the Biden Administration. It is included in the epilogue of my book, but I share it here as part of “the way forward” — an attempt to help improve our lives on this planet we all share. Objective # 1: To engage, educate and inform every American at the local level of relevant, tangible, and meaningful ways they can personally contribute to reducing carbon emissions; and Objective #2: To convert/retrofit every home and business to increase energy efficiency and achieve a carbon negative footprint simultaneously with the conversion of energy grids to clean alternatives. Objective #3: Applicable Federal and State institutions, both public and private, programs and existing funding, training, technical assistant, research shall be organized to support the local CAP. Objective #4: To give grassroots climate change advocates and institutions a purchase – ergo – focus to act locally in a structured local government program.

What is CAP and How Does it Work?

CAP is a local general-purpose government designed, administered and operated program aimed at increasing energy efficiency and reducing the carbon footprint for homes and businesses, and farming and ranching operations. The portal to gain access to the CAP is a single telephone number, email and smartphone app. It begins with a home (farm/ranching) audit and recommendation from the local CAP administrator for specific steps a homeowner can take to a) increase energy efficiency; and 2) lower the carbon footprint of homes and businesses based on a certification scale, A+, A and B rating. The CAP analyzes energy utilization and carbon sources in homes/businesses such as chlorofluorocarbons and other carbon or heat-trapping chemicals, refrigerants, oil and natural gas-powered heating systems, hot water heaters and other like appliances. It also examines energy-efficiency steps including wall and ceiling insulation, replacement double glazed windows and insulated doors or storm doors, and appliances with high energy utilization, and potential offsets like solar, geothermal and wind electric generating on-site technologies. Based on a uniform national devised rating system, the Administrator calculates the net increase in energy efficiency and reduction of carbon emissions. With alterations and improvements recommended, a ranking is assigned supported by a plan of action for each rank as follows: A+ is awarded for carbon reduction achieving Negative Carbon status; A is awarded for Carbon Neutral and Energy Efficiency status; and, B is Energy Efficiency Status only. The business/homeowner contacts a CAP Partner(s), to obtain preliminary cost estimates for each plan. The owner selects a Plan of Action for the rating selected and officially commits to implement the Plan. The rating is the CAP Certification assigned to the home or business that remains with the property, not its owners. The CAP Certification entitles owners to a variety of packaged incentives including discounts, tax subsidies, tax credits and a forward-pricing credit for resale of the home or business. Local development or building codes will be enacted by the CAP Administrator addressing new construction. All new construction will have to meet A rating. All resales of property that are not in the CAP program must either enter the program and complete upgrades before the sale or forward price the cost of CAP expenditures as a disclosed value on the MLS. Each CAP Administrator shall design the details of its own CAP through a local planning process (similar to the LWRCOG 208 water quality management planning in Northern Colorado (see “Gorilla in the Closet” Part III) and funded by federal grants-in-aid, public donations, dividends or taxes from a Cap and Trade-type economic approach to conversion of the energy grid to renewable energy undertaken by the State and federal government. The CAP shall be approved by the governor of each state and the lead federal agency. The Department of Housing and Urban Development shall be the lead federal agency for designated urban CAPs and the U.S. Department of Agriculture Natural Resource Conservation Agency shall be the lead federal agency for rural/agricultural CAPs.

Who are the Parties to the CAP?

Local city and county general-purpose government shall be eligible for CAP funding for program planning and administration. They will devise a locally designed plan for the CAP program and will carry out (administer) the functions of planning, management, operations and regulation. Operations functions, such as audits and the installation of equipment and upgrades according to the CAP ranking Plan of Action selected by the business/homeowner, may be delegated to CAP Partners, ergo other public and private entities.

Contributing Partners

The initial planning process shall include a local CAP citizens advisory committee consisting of a wide representation of stakeholders in the CAP planning area.

CAP Partners

CAP Partners are any public or private local entity that supports the determination of the Action Plans and packages and carries them out on behalf of the owners through a contractual relationship. This could include local lending institutions, equipment suppliers or venders, local contractors, building material suppliers, community colleges that may serve to assist in holding workshops for owners who want to enter the CAP, and any individual or party that wants to understand how the CAP works, its benefits and how it is administered. CAP Partners who enter the CAP and are approved by the Administrator and become preferred vendors/suppliers/contractors and may use this designation in their marketing and sales program.

Critical Success Factors

Create a standing New Environmental Federalism National Advisory Committee of state/local/business/civic nonprofits to guide and evaluate CAP success. Initiate demonstration projects based on existing successful case studies and willing participants (Demonstration Phase) Align federal and state agencies, the FED, banking institutions, real estate, trades, etc. to give full support to local general-purpose government . The Department of Housing and Urban Development and the Department of Agriculture shall take the lead federal role in rolling out and administering the CAP in urban and rural areas respectively. Kick-start and ongoing funding assistance to local governments. Source of funding shall be existing sources where possible. From the Biden Infrastructure Bill, dedicate $1 Billion to fund local city and county governments to engage in CAP set-up over a three-year program development term.

Implementation Strategy

Phase I: CAP Development and Demonstration Phase: Develop Federal/State CAP Features, policies and programs in support of Local CAP Planning. Create CAP guidance and training elements. Identify and fund Local city and county government collaborations in both urban and rural areas that will serve as demonstration case studies for full CAP rollout. Phase II: Planning: Fund 200 local government collaborations to undertake a two-year planning phase and one-year start-up phase, at 100% finding for three years, 50% for a fourth year, and 33% for implementation. Funding shall come from existing federal grant-in-aid programs, from the Biden Infrastructure Plan (once funded) and from revenues from a new Cap-and-Trade economic approach for conversion to clean and renewable energy. Depending on the federal Cap and Trade structure, funds will be in the form of revenues or taxes on polluting energy producers. Phase III: Implementation: Ongoing implementation.

by Eric Eidsness | May 3, 2021 | Blog

Here I engage in my own vanity by explaining my journey as an adult spanning more than 58 years. I referred to it earlier in my book as a “sheer strake,” a nautical term describing the arc of the lines of a ship from stem to stern. The shape and configuration of a sheer strake dictates the size, type and stability of the vessel. The great 7th Century Viking ships exhibited at the Viking Museum in Oslo, Norway is one of the most beautiful lines of a ship of any age. Its design allowed Leif Erickson to sail in an open vessel over rough seas, often through ice flows, powered by a single sail for weeks if months at a time, anywhere in the world across vast stretches of the Atlantic Ocean.

At the stern is Vietnam, at midships my service in EPA and career in the private sector, and on the bow the publishing of this book and what may follow. My life’s arc began as a 25-year-old ensign in the United States Navy and my experience and lessons learned from the American War in Vietnam. I was disabused by my own generation upon my return as a “baby killer.” This haunted me.

At the stern is Vietnam, at midships my service in EPA and career in the private sector, and on the bow the publishing of this book and what may follow. My life’s arc began as a 25-year-old ensign in the United States Navy and my experience and lessons learned from the American War in Vietnam. I was disabused by my own generation upon my return as a “baby killer.” This haunted me.

At the stern is my early education followed by Vietnam, at midships my service in EPA and career in the private sector, and on the bow the publishing of this book and what may follow. My life’s arc began as a barefoot Florida cracker in the 1950’s segregationist era who was sent away to boarding school in New England where my most of my schoolmates came from wealthy families. There at 16 and having been derided as a “rebel,” I raised the Confederate Battle Flag calling out the racism and bigotry I saw in New England. After graduating from Vanderbilt Engineering School I was drafted out of the Peace Corps and received a commission in the United States Navy. My service in combat in the riverine forces in the American War in Vietnam taught me to challenge the policies of my government to which I did not agree. This included the waste, fraud, and abuse resulting from Congress cutting blank checks. Upon my return to the San Francisco Bay area, I was disabused by my own generation as a “baby killer.” This haunted me.

I returned to my career as environmental engineer in EPA’s predecessor in Atlanta in 1970 and wrote EPA’s first environmental impact statement. I allied with a local grass roots movement to “Save the Chattahoochee River.” I left the EPA because government wasn’t for me — I was uncomfortable telling city and county officials and their consulting engineers that they had to do it EPA’s way or not get grants for the construction of sewerage works. I joined the Boston-based prestigious Arthur D. Little, Inc. in 1973 and learned the skills of being a manager. In 1975 I joined a regional planning program under the CWA in northern Colorado and cemented my career representing local governments in the environmental field.

In 1981 I joined the EPA as Assistant Administrator for Water because I didn’t want to go to the grave not knowing what it was like to establish and oversee my own national policies on water quality. “Sewergate” (1981-1983) was a hard lesson and in 1983 I returned to the private sector to support two households, and worked hard to make my three young children as safe and supported as possible. I let brass rings go by.

9/11 happened, I was in mid-town Manhattan that morning. What horror! My son, 18 years old, joined the U.S. Marines and became a crew chief. Bush invaded Iraq on a false pretense and his Secretary of Defense disbanded Saddam Hussain’s armed and organized Republican Guard. Chaos ensued and mullahs who run the streets with armed insurgents took over — then Isis filled the void. We just kept spending.

40 years after leaving Vietnam in 1969, I returned to my operating area in the I-Corps. The communist government virtually cleansed Vietnam of any evidence of American occupation, with few exceptions — a museum at the Advanced Marine Fire Base Khe Sanh. They tried to overrun it, just as they tried to overrun the Marine Fire base at Cua Viet. I was there. It is a young country and there are few alive who were present when we destroyed their country and killed an estimated three million Vietnamese, all told. The scars of Agent Orange around Khe Sahn and the generations of deformed babies resulting from its debilitating chemicals remains. The America governments has offered nothing as reparations. All these things bothered me.

After sponsoring a town hall meeting of more than 750 local citizens called America in Iraq in late 2005, my panel of four experts discussed the Middle East and military deployments. Tom Sutherland, who was captive of the Islamic Jihad who threatened to cut his head off for the six years he was in captivity, predicted the outcome if the U.S didn’t stop bullying our allies to join the “Coalition of the Willing” and trying to bring democracy at the point of a gun. I had enough and re-entered public life and ran for Colorado’s fourth congressional seat against an evangelist who wanted to control what Americans did in their bedroom and interfere with family decisions, and a liberal African-American former professional basketball player and college administrator. I won 11.3% of the vote in what was a 2-month long campaign and earned the endorsement of four of the six daily newspapers. My campaign website is now in the Archives of the Library of Congress.

Finally, this book was spawned when I was insulted by my college professor in coursework I took in my sixties. He called me and my EPA colleagues under Reagan a “bad person”. My governing principles, my interest in history which I have lived and been a part of in the environmental field, and my life’s experience are my best defense from the criticism of those I have offended and who don’t agree with my views. Yet, I am going to offer President Biden and his advisors some advice, something their advisors don’t understand that has been baked into their thinking as part of their roles as leaders in the environmental field — and that is to forsake hierarchical thinking and reconfigure the EPA in a bottom-up, inclusionary approach to governance.

At the stern is Vietnam, at midships my service in EPA and career in the private sector, and on the bow the publishing of this book and what may follow. My life’s arc began as a 25-year-old ensign in the United States Navy and my experience and lessons learned from the American War in Vietnam. I was disabused by my own generation upon my return as a “baby killer.” This haunted me.

At the stern is Vietnam, at midships my service in EPA and career in the private sector, and on the bow the publishing of this book and what may follow. My life’s arc began as a 25-year-old ensign in the United States Navy and my experience and lessons learned from the American War in Vietnam. I was disabused by my own generation upon my return as a “baby killer.” This haunted me.